This exhibit examines the impact of colonialism on indigenous communities, focusing on private land ownership, individualism, and the importance of communal systems and land rights.

The Legacy of Colonialism: Land, Individualism, and Indigenous Resistance

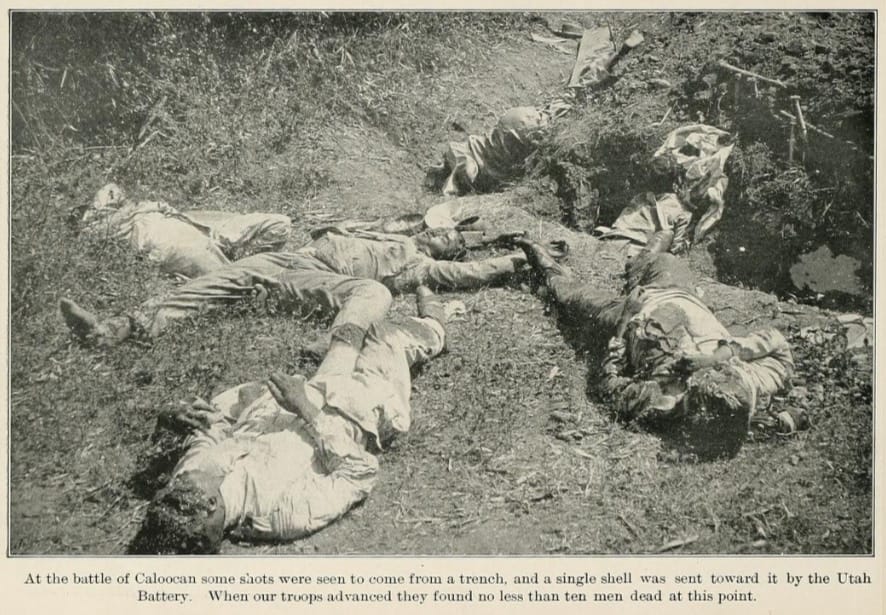

The history of Spanish and American colonialism in the Philippines highlight the profound injustices inflicted upon indigenous populations by the imposition of socioeconomic concepts serving the colonial project.

The introduction of private land ownership, violent Christening, suppression of indigenous beliefs, and exploitative tax collection are examples of grave violations that left lasting scars on affected societies.

The desire to establish trade and cultural exchange should always be rooted in mutual respect and consent, ensuring that the benefits are shared equitably. Historical records and contemporary experiences reveal the colonial propaganda lies.

Observations on the challenges faced by native communities across the globe are poignant and highlight the enduring impacts of colonialism. The marginalization and suppression of these communities are tragic consequences of historical and ongoing injustices.

Reconstructing cultural identity and achieving decolonization is a complex and daunting task. Despite the immense challenges they face, indigenous communities are actively working to preserve and revitalize their cultures, languages, and traditions.

The largest obstacle to success is the concept of private land ownership. A peaceful and sustainable future through the deconstruction of private property is a vision shared by those who seek to challenge the status quo and build an egalitarian, just and equitable world. This perspective on land rights leads to the struggle for the deconstruction of private property. The idea that natural resources should belong to all of humanity and not be subject to private ownership is a powerful one, and it aligns with the principles of collective wellbeing, sustainability, and environmental justice.

Indigenous Land Rights Movements

Many indigenous communities around the world are fighting for the recognition and restoration of their ancestral lands. Indigenous peoples often have a deep connection to their land and play a crucial role in environmental conservation. Recognizing and supporting their land rights can contribute to more sustainable and equitable management of natural resources. For example, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s resistance against the Dakota Access Pipeline highlighted the importance of protecting sacred lands and water resources.

The struggle for land rights is a critical issue, as it directly impacts the livelihoods, cultures, and autonomy of indigenous and marginalized communities.

The Waray concept of Tiklos

The Waray concept of Tiklos is a fascinating example of how communal and cooperative structures were integral to many indigenous cultures before the arrival of colonial powers. Tiklos, a traditional form of community labor exchange among the Waray people of the Philippines, embodies the principles of mutual aid and collective effort.

In the Tiklos system, community members would come together to help each other with various tasks, such as farming, building houses, or other communal projects. This cooperative approach ensured that everyone in the community had the support they needed, and it fostered strong social bonds and a sense of solidarity.

The arrival of American colonialists in the early twentieth century disrupted these traditional systems, imposing new economic and social structures that prioritized individualism and private property. This shift had profound and often devastating effects on indigenous communities, undermining their communal ways of life and eroding their cultural identities.

The Zapatista approach

The Zapatistas, an indigenous revolutionary group in Chiapas, Mexico, has taken an approach that, with its emphasis on communal land ownership and collective management, resonates with these traditional systems like Tiklos. It serves as a reminder of the value of cooperative and community-oriented practices, and it offers a powerful alternative to the dominant narratives of individualism and private property.

Key aspects of the Zapatista approach:

- Communal Land Ownership: Land is not owned by individuals but by the community as a whole. This ensures that everyone has access to the resources they need to live and thrive.

- Community Management: Decisions about land use and management are made collectively through participatory processes. This empowers community members and ensures that their needs and perspectives are taken into account.

- Housing as a Human Right: Housing is considered a fundamental human right, and the community works together to ensure that everyone has a safe and adequate place to live. This collective effort strengthens social bonds and fosters a sense of solidarity.

- Rejection of Individualism and Consumerism: The Zapatistas emphasize the importance of collective wellbeing over individual success. By rejecting consumerism and individualism, they create a society where individuals can flourish in harmony with the collective.

- Symbiosis with the Collective: The Zapatista model promotes the idea that individuals thrive when they are part of a supportive and cooperative community. This symbiotic relationship between the individual and the collective is central to their vision of a just and equitable society.

The Zapatista approach offers valuable insights into how land and resources can be managed in a way that prioritizes collective wellbeing and sustainability. It challenges the dominant narratives of private property and individualism, and provides a compelling alternative that emphasizes community, cooperation, and mutual support.

The Concept of Individualism

An American statement on introducing and teaching individualism in Moroland [U.S. collective name of the Philippine provinces Zamboanga, Lanao, Cotabato, Davao, and Jolo] gives critical insight into the broader agenda of colonial powers. This strategy of dividing people to maximize exploitation is a fundamental theme in colonial history. By breaking down traditional communal systems and imposing new social and economic structures, colonial powers could more effectively extract resources and labor from the colonized regions.

In the case of Moroland, the imposition of individualism disrupted the existing social fabric, which was based on communal cooperation and mutual support. This not only facilitated economic exploitation but also weakened the resistance to colonial rule by fragmenting the community.

Understanding these historical dynamics is crucial for recognizing the long-term impacts of colonialism and the ways in which it continues to shape contemporary societies. It also underscores the importance of supporting efforts to revive and strengthen communal and cooperative practices that prioritize collective wellbeing.

Deconstructing the Development Narrative

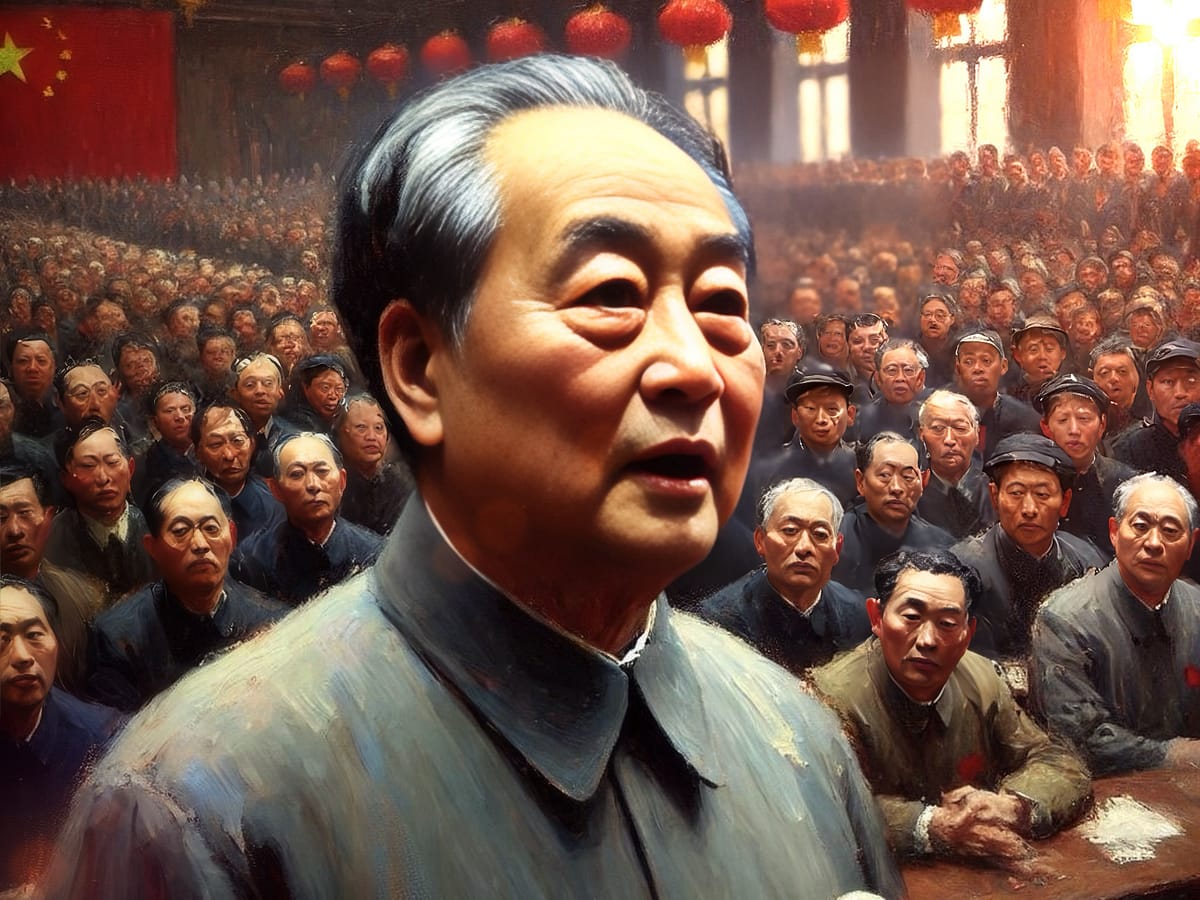

The 21st century Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) demonstrates how development can be achieved through non-aggressive methods, that offer real mutual benefits. This is an approach that challenges the colonial narrative that infrastructure improvements necessitate hostile intervention.

The BRI aims to enhance global trade and stimulate economic growth across the world by investing in infrastructure projects such as roads, railways, ports, and airports. These projects are developed through partnerships and agreements with the host communities, emphasizing cooperation and mutual benefit.

This model shows that infrastructure development can be pursued in ways that respect the sovereignty and interests of all parties involved. It also highlights the potential for international cooperation to address global challenges without resorting to aggression or exploitation.

The BRI example effectively highlights the contradictions in the US imperialist narrative of bringing “peace, stability, and infrastructure.”

The Moroland Case

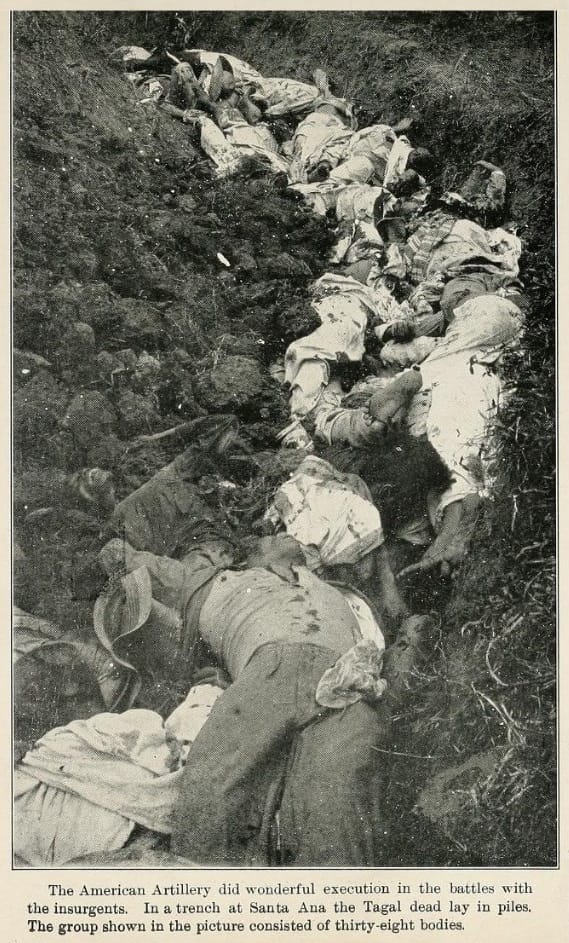

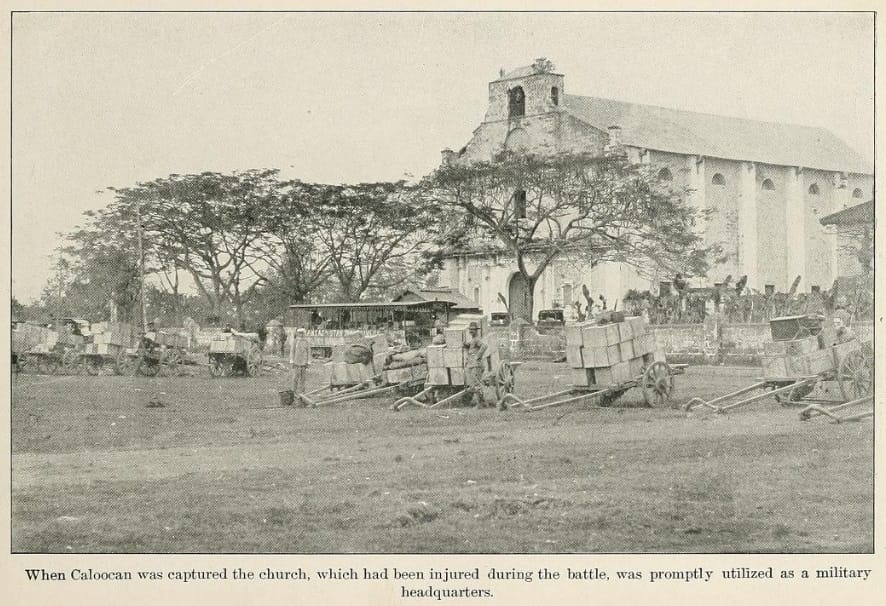

The situation in Moroland, where local warlord rivalry and lack of infrastructure were used to justify military intervention, underscores the complexities and often devastating consequences of such actions.

The US so called “civilization project” in Moroland was marked by military invasion, with systematic destruction, violence and immense suffering, which vastly exacerbated the very issues it claimed to address. This pattern is not unique to Moroland, but can be seen in various contexts where military interventions have led to prolonged conflict and instability rather than genuine peace and development.

Concluding statement

The conclusion is that, by focusing on mutual benefit and respecting the sovereignty and agency of local communities, it is not only possible to achieve sustainable development and peace without resorting to aggression, but it is also the least inhumane path to progress.

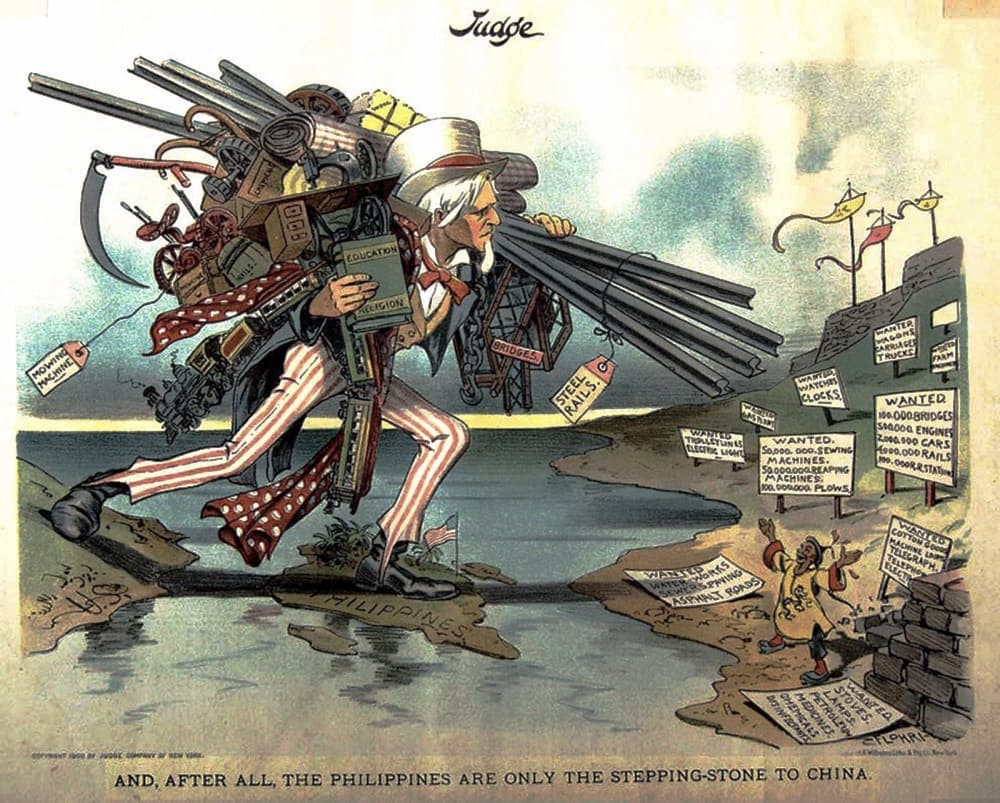

Featured image: AND, AFTER ALL, THE PHILIPPINES ARE ONLY THE STEPPING-STONE TO CHINA. Editorical cartoon from after USA conquest of the Philippines. Uncle Sam is seen stepping across the ocean into the Philippines loaded down with symbols of modern civilization, including books labeled “Education” and “Religion”, bridges, railroad trains, sewing machine, farm machinery. A short distance beyond the Philippines a small figure representing China stands with a happy expression and open arms, surrounded by signs saying large quantities of modern goods are wanted. [Source: Wikimedia]

This web site definitely has all the information I needed concerning this subject and didn't know who to ask.

Keep on working, great job! Here is my homepage 스포츠 하이라이트 보기

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

What is it to doubt? It's a metaphorical biblical reference by an anonymous Tagalog poet.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope…