The population census conducted in the Philippines in 2010 for the first time included an ethnicity variable but no official figure for Indigenous Peoples has been released yet. The country’s Indigenous population is estimated to be about 20 million of the national population of 100 million, based on the 2015 population census.

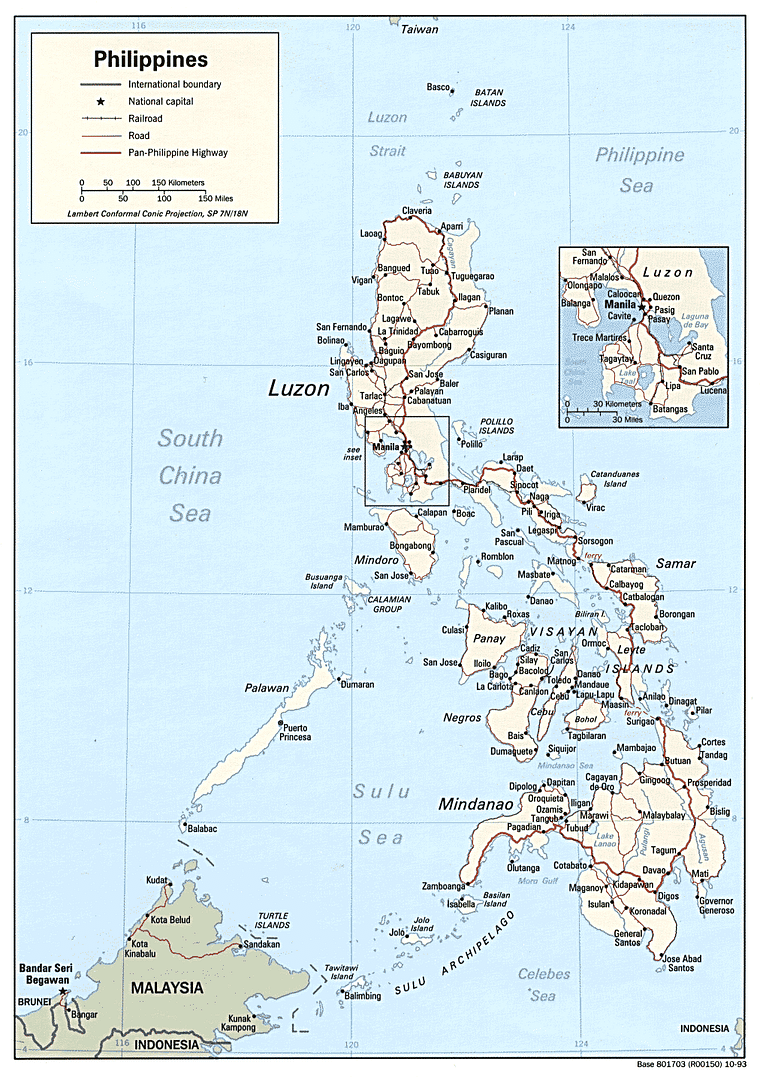

The Indigenous peoples organize in geographical group collectives covering the majority of tribes in each region: in the northern mountains of Luzon (Cordillera) as Igorot and in southern Mindanao as Lumad. There are smaller groups collectively known as Mangyan in the island of Mindoro as well as smaller, scattered groups in the Visayas islands and Luzon, including several groups of hunter-gatherers in transition.

Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines have retained much of their traditional, precolonial culture, social institutions and livelihood practices. They generally live in geographically isolated areas with a lack of access to basic social services and few opportunities for mainstream economic activities, education or political participation. In contrast, commercially valuable natural resources such as minerals, forests and rivers can be found primarily in their areas, making them continuously vulnerable to development aggression and land grabbing.

The Republic Act 8371, known as the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA), was promulgated in 1997. The law has been lauded for its support for respect of Indigenous Peoples’ cultural integrity, right to their lands and right to self-directed development of those lands. More substantial implementation of the law is still being sought, however, apart from there being fundamental criticism of the law itself. The Philippines voted in favour of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), but the government has not yet ratified ILO Convention 169.

The situation of Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines is worsening under the Duterte-regime. Development aggression has intensified, with various mining, energy and other so called ‘development’ projects encroaching on Indigenous territories. Human rights violations are likewise escalating, with Indigenous activists comprising most of the victims. In 2019, the international watchdog Global Witness has declared the Philippines as the world’s deadliest country for environmental defenders, with 30 deaths recorded in 2018.

China-funded projects violating Indigenous Peoples’ rights

After the Philippine government signed numerous loan agreements with the government of China in 2018, various issues hounded the loan agreements for the Chico River Pump Irrigation Project (even though construction started the same year) and the Kaliwa Dam project. Both projects are located in Indigenous territories in the Cordillera and Cal- abarzon regions affecting at least 3,765 Indigenous people. The loan agreements for these projects have not been disclosed to the public and have stirred criticism when leaked copies reached the public in 2019. Cordillera Peoples Alliance (CPA) denounced the onerous and lop- sided loan agreement between the governments of the Philippines and China for the project, which CPA characterised as a debt trap for the Filipino people and a sell-out of the country’s sovereignty.

Meanwhile, opposition to the China-funded Kaliwa Dam project has intensified as the project will displace over 1,400 Indigenous Dumagat families and affect more than 100,000 peoples. Despite the threats to Indigenous communities and the massive damages to the environment and biodiversity that the project may cause, President Duterte declared he would use ‘extraordinary powers’ to ensure that the project will push through. Indigenous Peoples and various groups also criticised the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) for issuing an environmental compliance certificate despite stiff opposition to the project.

On April 4 and May 9, petitions were lodged by the Makabayan Bloc, KATRIBU national alliance of Indigenous Peoples and environment advocates at the Philippine Supreme Court. The petitions were attempts to stop the implementation of the loans for the Chico River Pump Irrigation and Kaliwa Dam projects, since several provisions of the loan agreements violate the 1987 Philippine Constitution. These violations include the confidentiality clause, the choice of Chinese law as governing law, the selection of an arbitration tribunal in Hong Kong and the waiver of sovereign immunity over Philippine patrimonial assets of commercial value. On the Chico River Pump Irrigation Project, the Malacanang Palace said it will comply with the Supreme Court’s order for the government to respond to the petition against the project but insisted that the loan deal is constitutional. To date, Cordillera Indigenous Peoples do not know if the government has made any response.

Another China-backed flagship project of the Duterte administration that outrightly disregarded Indigenous Peoples’ rights is the New Clark City, which is envisioned by the government to be the first smart and green city in the country. The first phase of the project, which housed a “state-of-the-art sports facility” that was used during the 2019 South East Asian Games, has already displaced over 27,500 members of the Aeta Indigenous people. Expansion of the project threatens to displace around 500 Aeta families. The Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA), a government-owned corporation under the Office of the President that is mandated to strengthen the country’s Armed Forces while building cities, maintains that the Aetas are not displaced as there are no Certificates of Ancestral Domain Titles in the area.

The latest deal between the Chinese government’s Belt and Road Initiative and the Duterte administration’s Build, Build, Build infrastructure program is the proposed 250-megawatt South Pulangi Hydroelectric Power Plant (PHPP) project, which will flood 2,833 hectares of Indigenous lands in four towns near Davao City and will affect residents of 20 communities. The USD$800 million contract agreement between PHPP CEO Josue Lapitan and China Energy Engineering Co Ltd Chairman Dong Bin was signed in April 2019 without the consent of the affected communities. For many years the Indigenous Peoples’ opposition to the PHPP has been met with militarisation, harassment, indiscriminate firing and extrajudicial killing.

Mining and other energy projects

Large-scale mining remains a constant threat faced by Philippine Indigenous Peoples. In August 2019, Cordillera Indigenous Peoples formed the Aywanan Mining and Environment Network in opposition to the mining applications of the Cordillera Exploration Company, Inc. (CEXCI), a subsidiary of Nickel Asia Corporation in partnership with Japan-based Sumitomo Metal Mining Co. Ltd. CEXCI’s mining applications cover 72,958 hectares of land in the ancestral lands of the Indigenous Peoples in the Cordillera and parts of Ilocos Sur. Petition-signing against the mining applications of CEXCI started in August 2019 and is continuing.

In Didipio, Nueva Vizcaya, a people’s barricade which started in July 2019 led to the temporary suspension of the gold and copper mining operations of multinational company OceanaGold. The company’s mining permit (Financial and Technical Assistance Agreement) expired in June 20 after 25 years of operation. Pending the renewal of its permit to operate, the company appealed to continue its operations but this was denied in a regional trial court. Communities affected by the mining operations opposed the renewal of the company’s mining permit. They have long been complaining of the environmental destruction and human rights violations committed by OceanaGold. In Mindanao, the Lumad Indigenous Peoples continue to oppose at least three mining tenements that were approved by the government and cover around 17,000 hectares in the Pantaron mountain range, which straddles the provinces of Davao del Norte, Davao del Sur, Bukidnon, Misamis Oriental, Agusan del Norte and Agusan del Sur. The Pantaron range is the main source of the major watersheds in the region.

In the energy front, aside from hydropower projects that the Duterte administration continues to build, the Kalinga geothermal project of Aragorn Power and Energy Corporation and Guidance Management Corporation, in partnership with global energy company Chevron, is about to complete its exploration stage. The project covers 26,139 hectares in Kalinga province.

Escalating attacks against Indigenous Peoples’ organisations and human rights defenders

Following the issuance of Executive Order 7022 by President Duterte in December 2018, the Duterte regime has intensified attacks against Indigenous Peoples through the formation of the Task Forces to End the Local Communist Armed Conflict. Executive Order 70 is part of the government’s “whole-of-nation” counter-insurgency operation plan which has an “Indigenous People”-centric approach. The attacks are meant to quell Indigenous Peoples’ resistance to development aggression and government policies that violate Indigenous Peoples’ rights, and results in further marginalisation of Indigenous Peoples in the country.

In the implementation of Executive Order 70, the Department of Education ordered the closure of 55 Lumad schools, leaving 3,500 students and more than 30 teachers out of school and jobs. The closure order was on baseless claims of the government that the Salugpongan schools are teaching students to rebel. The Lumad Indigenous Peoples decried this injustice that only deprives Lumad children of their right to education.

Strategies of disinformation are being used by other government agencies, such as the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) and Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA), and presidential agencies like the Presidential Communications Operations Office (PCOO), Office of the Presidential Adviser for the Peace Process (OPAPP) and the National Intelligence Coordinating Agency (NICA). Political dissenters are politically vilified and tagged as communists or members of the New People’s Army (NPA).

In a series of briefing sessions on the Whole of Nation Approach to government agencies in Baguio City, NICA has been presenting Indigenous Peoples’ organisations and Indigenous Peoples human rights defenders as Communist Terrorist Groups and members of the NPA. UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, Vicky Tauli-Corpuz, and some leaders of the CPA were accused of being infiltra- tors to the UN on behalf of the Communist Party of the Philippines and the NPA.

In a congressional briefing on 5 November 2019, Indigenous Peoples’ organisations such as the CPA, humanitarian organizations such as the Citizens’ Disaster Response Center and Oxfam Philippines, and the National Council of Churches in the Philippines were labeled by the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Department of National Defense as communist terrorist groups.

The dangerous labelling of Indigenous Peoples’ organisations and human rights defenders as communist terrorist groups and members make them vulnerable to various forms of human rights violations. As of August 2019, eightysix Indigenous people have fallen victim of extrajudicial killings (at least nine victims in 2019), 66 Indigenous people were victims of frustrated extrajudicial killings (at least eight victims in 2019), 36 are political prisoners, and 31,004 were victims of forced evacuation since Duterte assumed the presidency in July 2016.30 Many of the victims were opposing development aggression, human rights violations and the policies of the government that violate Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

Indigenous Peoples’ advocates were not spared from the tyranny of the Duterte regime. Brandon Lee, a Chinese-American volunteer of the Ifugao Peasant Movement in the Cordillera region, has been brand- ed as an enemy of the state and was shot in front of his house in August 2019. He is now back home in the United States for his recovery.

The criminalisation of Indigenous human rights defenders is continuing. From 2016 to August 2019, trumped-up charges caused the arrest and detention of at least 196 Indigenous people, 36 of whom remain unjustly imprisoned. Datu Jomorito Guaynon, chairperson of Kalumbay Regional Lumad Organization remains in prison after he was arrested due to fabricated criminal charges. Rachel Mariano, a health worker of the Community Health, Education, Services and Training in the Cordillera Region, was acquitted in September 2019 after a year of detention. However, the judge who acquitted her, Mario Bañez, was shot dead two months later.34 Mariano still faces other fabricated charges and is out on bail.

After two-and-a-half years, the Martial Law in Mindanao was lifted on 31 December 2019. However, according to the Armed Forces of the Philippines, it will remain under a state of emergency by virtue of Proclamation No. 5536 which was issued in 2016. Indigenous Peoples thus fear that the situation will not change much since the proclamation allows military and police forces to impose checkpoints and curfew. They fear that the continued significant presence of the government’s armed forces in Mindanao and military operations will continue to protect investments in Indigenous territories.

Bringing the issues to the United Nations

Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines look forward to the UN probe on the human rights situation in the country. In preparation for the UN probe and for other international engagements, Indigenous Peoples human rights defenders representing various Indigenous Peoples’ organisations gathered in November 2019 for the national consultation workshop on the issues faced by Indigenous Peoples.

The national consultation workshop consolidated the data on the situation of human rights and economic, social and cultural rights of Indigenous Peoples, which was presented during the Asia Consultation with UN Special Rapporteur Vicky Tauli-Corpuz in November 2019. It also served as the basis for the Philippine Indigenous Peoples’ submission to the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights to contribute in the UN Human Rights report on the Philippines.

The struggle continues

Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines are further strengthening their organisations and their struggles for human rights and Indigenous Peoples’ rights towards facing the challenges in the next year.

Source: The Indigenous World 2020, The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA).